|

|

|

|

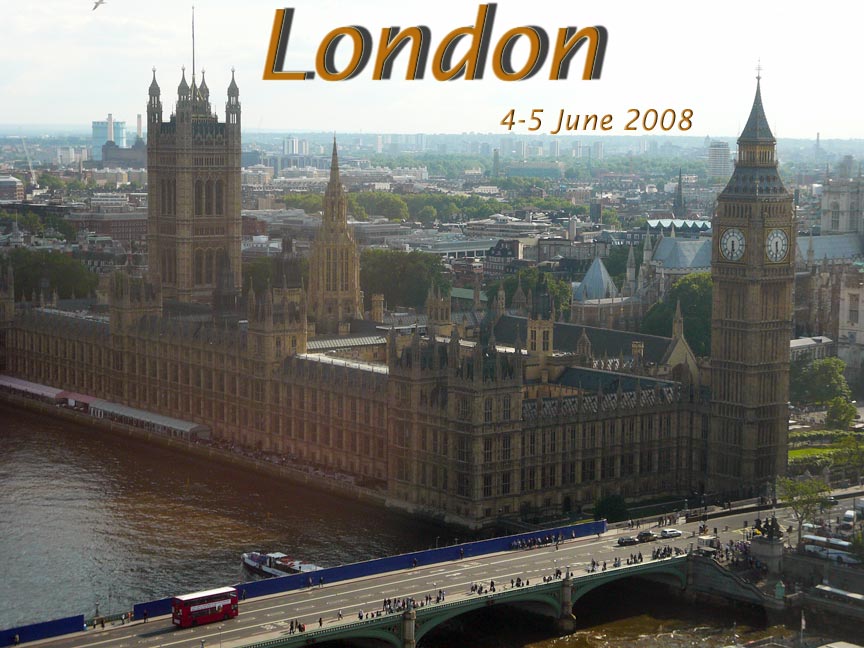

From Islamabad we flew to London and spent a little more than

one day. We started with a ride on the London Eye on the left. It provides a

spectacular view of London. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the evening we ate in a pub. Since smoking is no longer

allowed, pubs installed street counters for smokers who have to smoke outside

on the sidewalk. |

|

|

|

After all the fuss about the da Vinci code (Dan Browns book),

we decided to visit the Temple church of the Templars. On the left is the

beautiful Romanesque entrance portal of this late 12th c. church. |

|

Inside this round church based on the Church of the Holy

Sepulchre in Jerusalem there are a number of tombs. |

|

|

|

One of the major reasons we wanted to stop in London was to

visit the British Museum again. We found this vivid Tibetan Tantric sculpture (early 19th

c). Depicted is Yamantaka Vajrabhairava, a fierce Tantric deity for

overcoming evil and death. He is a frightening manifestation of Manjusri –

the Bodhisattva of knowledge. Yamantaka has become the tutelary deity of the

Dalai Lamas and of the Gelugpa (Yellow Hat) school of Tibetan Buddhism.

Yamantaka is shown embracing Vajravarahi his wisdom partner. Their union

represents the spiritual passion for enlightenment. |

|

On the right is a stoneware figure of Budai dating from 1486

(Ming Dynasty). Budai, the fat smiling monk, is an accretion of several

Chinese Buddhist legends. He is sometimes regarded as and incarnation of

Maitreya the future Buddha who will follow Shakyamuni. It is in this role

that Budai is placed in the entrance halls to temples and monasteries. We’ve always been told that rubbing this ubiquitous fat and happy

monk’s tummy brings good luck. The Chinese think that being fat is a sign of the

prosperity they wish. However, in the British Museum we learned that he

sometimes is a Buddha image! |

|

|

|

Our most fascinating find was an assortment of Assyrian stone

reliefs from Nimrud dating from about 865-860 BCE. King Ashurnasirpal II appears twice, dressed in ritual robes

and holding the mace symbolizing authority. In front of him is a sacred tree

(symbolizing life) and he makes a gesture of worship to a god in a winged

disc. The god (perhaps the sun god Shamash) has a ring in one hand; this is

an ancient Mesopotamian symbol of god-given kingship. |

|

What we found so fascinating is the depiction

of the god in the winged disc. The Zoroastrian tradition, rigidly codefied

under the Sassanian rule (2nd through 6th c. CE), calls

it a Fravahar or guardian soul and gives extensive symbolic meaning to all of

its components (wings, ring etc). See our Iranian website. This ancient Mesopotamian deity was adopted

some 300 years later by the Achemenids where it is found abundantly (see the

tombs of Naqsh-e-Rostam and Persepolis). There is no mention in any of the

Achemenid writings of Zoroaster. It seems likely that when Zoroastrianism

became a formal religion much after the Achemenids, this Mesopotamian deity

was also incorporated into that tradition. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|